Life in Minneapolis and St. Paul has changed dramatically since the sawmills sprang up around St. Anthony Falls, the gangsters hid out in the Wabasha Caves, and the Foshay Tower first pierced the horizon. Could the founders have foreseen their downtowns would one day be linked by light rail? Perhaps, but if so, surely not with an app to track the next train’s arrival.

To get a sense for how the Twin Cities will look and feel in the coming decades and what it will be like to live in them, we asked experts who forecast the future—in demographics, economics, energy, transportation, and other key areas—to name the trends and changes they believe will have the greatest impact on the way we live, work, move, and play.

Their predictions include everything from the marked aging of the population to the arrival of self-driving cars—some of which are anticipated with more certainty than others. But of all the unknowns about the decades ahead, one thing is certain: As the metro’s influence grows, both within the state and around the world, there will be plenty at stake in how change occurs.

Who We’ll Be

More People

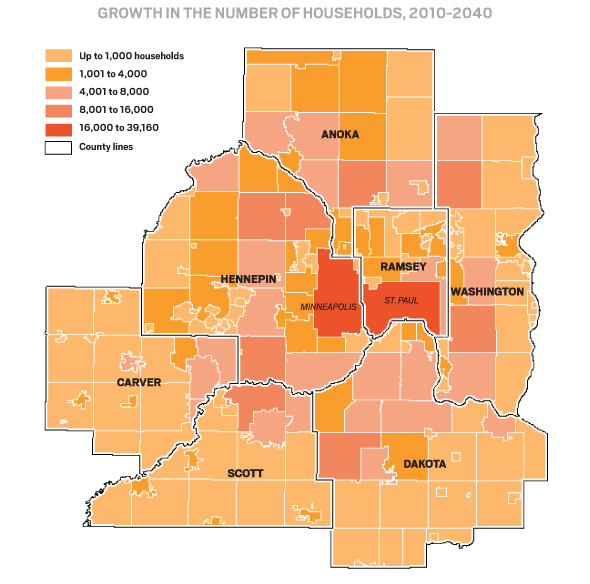

By 2040, the Twin Cities metro area will add 824,000 new residents to the 2,850,000 counted during the 2010 census, according to projections from the Metropolitan Council, the agency responsible for policymaking, planning, and shared services of the Twin Cities region. Natural population growth will account for most of the change, but nearly a third of the increase will be driven by migration, including the arrival of some 355,000 international immigrants.

Art by Noelia Lozano

A Dramatically Aging Population

The massive baby-boomer generation is aging into the senior cohort and living longer; at the same time, the birth rate is half what it was in the 1950s—factors pushing the Twin Cities toward a generational tipping point at which there will soon be more seniors than children. The 2010 census found 11 percent of metro residents were age 65 and older while 20 percent were age 14 and under. By 2040, the Met Council predicts that the senior population will nearly double to make up about 21 percent of the population, while 19 percent of the population will consist of children. “A future of more senior citizens than children is a phenomenon that we haven’t seen before,” explains Libby Starling, the Met Council’s manager of regional policy and research.

Her colleague Todd Graham, a forecaster with the council, is quick to note that as people put off retirement and live longer, 65 won’t be the milestone it once was. “Don’t expect that people are going to immediately change where they’re living and in what kind of home,” he says. “They’ll remain important in our civic life and our workplaces and will probably have a lot more say as a consumer group.”

Greater Diversity

In 2010, people of color made up 24 percent of the metro’s population. By 2040, the Met Council expects that number to grow to 40 percent, with international immigration making a substantial contribution to the change. “We can’t predict who the next big group of international immigrants will be,” Starling says. “But what we do feel comfortable saying is that the Twin Cities will continue to attract people moving to this country from different parts of the world, due to job opportunities and our reputation for welcoming international residents to our region.”

Chart via Metropolitan Council Thrive 2040 Forecast

Smaller Households

Of the nearly 400,000 new households the Met Council expects will be added, roughly 175,000 are expected to consist of people living alone and another 170,000 will be home to couples without children. The remaining 47,000 or so households will be families with children. “The growth is so skewed toward adding households that don’t have children that it will change the demands that are registering with developers and builders,” Graham says. “It’s moving slowly, like a very large glacier, but it’s certain that it’s moving in that direction.”

Where We’ll Live

CHART VIA METROPOLITAN COUNCIL THRIVE 2040 FORECAST

Greater Density

Both historic core cities reached their population peaks in the 1950s—with Minneapolis and St. Paul at just more than 500,000 and 300,000 respectively—and then both began ceding population growth to the suburbs. Beginning in 2010, though, when Minneapolis’ population was right around 380,000 and St. Paul’s close to 295,000, the tide began to shift as the cities made rapid population gains for the first time in decades. By 2040, the Met Council projects that Minneapolis will add about 105,000 residents and St. Paul 54,000.

This shift reflects a long-term global trend for cities’ increasing influence: By 2050, projections suggest that 75 percent of the world’s population will live in urban areas. As dean of the University of Minnesota’s College of Design, Tom Fisher concerns himself with both the built environment and the cultural attitudes that impact it. “Two of the biggest demographic groups—the baby boomers and millenials—are both increasingly oriented to living in the cities rather than moving out to the suburbs,” he notes. “Our ability to compete globally is going to depend on how active and innovative our cities are; having nice suburbs isn’t going to be as important as having talented innovators working together in cities. We need to have our cities be as attractive to live in as possible to attract talent we need to compete.”

Taller, Smaller, More Flexible Living Quarters

Housing in the Cities’ urban cores will continue to take on more characteristics of larger cities. Caren Dewar and Cathy Capone Bennett of the Urban Land Institute of Minnesota, a nonprofit focused on creating sustainable communities, spell out some of those specifics. Frequent moves will increase the demand for rental housing; units will have smaller footprints but more flexible design (the ability to convert rooms for different uses); and as demand for larger homes decreases, existing houses will be subdivided into smaller units in the same manner as urban mansions from the turn of the century.

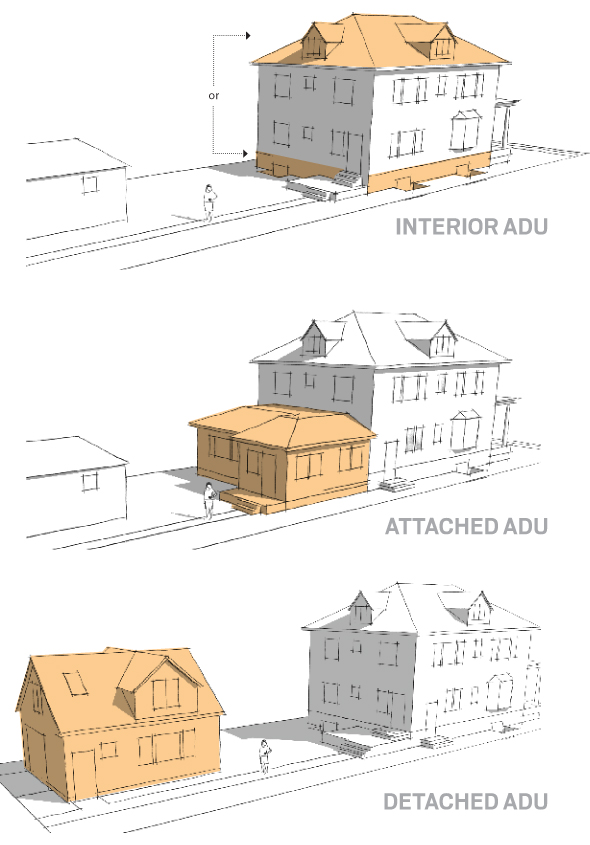

The construction of taller towers near downtown and mid-rise buildings in activity centers and along transit corridors is expected to be a long-term trend. And the increasing senior population will drive demand for townhomes and age-restricted communities as well as smaller, single-family detached homes that are association-maintained. Because Minneapolis and St. Paul are alley-oriented cities, they’re well-poised to increase density in single-family residential neighborhoods with minimal negative impact by allowing Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), self-contained residences with separate entrances but on the same lot. “We used to live this way,” Fisher notes. “Generations of families have long lived together. We shouldn’t see ADUs as some sort of communist plot—they’re as American as you can get.”

Getting Around

More Public Transit

Between 2004 and 2011, transit ridership in the Twin Cities grew nearly 40 percent and there are many corridors with enough demand to justify improved service, with faster trips, more frequency, and more stations. Buses will fill much of this need, but in the near future, expansions of the Green and Blue LRT lines are in the works with the Southwest (2018–2019) and Bottineau Boulevard Transitway (2021) lines.

Fewer Cars, Less Traffic

Congestion is one of the greatest banes of urban life, but there are signs that the future may bring gridlock relief. The fact that most cars sit idle 90 percent of the time offers substantial opportunity for garnering more usage from fewer vehicles. Car-sharing services (HOURCAR, Car2Go, Zipcar and Enterprise CarShare) have expanded rapidly since they launched in the Twin Cities in 2005, and app-enabled ride services such as Lyft and Uber X allow car owners to generate income from their vehicles by operating as independent chauffeurs.

Congestion is one of the greatest banes of urban life, but there are signs that the future may bring gridlock relief. The fact that most cars sit idle 90 percent of the time offers substantial opportunity for garnering more usage from fewer vehicles. Car-sharing services (HOURCAR, Car2Go, Zipcar and Enterprise CarShare) have expanded rapidly since they launched in the Twin Cities in 2005, and app-enabled ride services such as Lyft and Uber X allow car owners to generate income from their vehicles by operating as independent chauffeurs.

Met Council transportation planner Mark Filipi expects that digital technologies will enable more formalized versions of the ride-sharing that happens in congested areas on the coasts, when solo drivers give strangers a ride in order to access the carpool lane—a sort of white-collar hitchhiking known as “slugging.” New apps can link travelers headed in the same direction in the same manner as online dating sites. “The younger generations are a lot more comfortable using electronic media as a means to make those connections,” Filipi says.

As people increasingly live closer to work or work more from home, Fisher makes the surprising forecast that driving might decrease to the point that there will soon be an excess capacity of highways and parking garages. “I predict that in the next decade the conversation is going to be, ‘What infrastructure do we take out?’” he says.

Self-Driving Cars

Met Council transportation planner Mark Filipi’s prediction may burst a few bubbles: “I don’t foresee even out to 2050 that we’ll be getting the Jetsons air cars,” he says. But manufacturers are planning to launch driver-less cars by 2020, and Filipi notes the potential benefits in terms of reducing accidents and congestion as well as allowing the elderly to maintain their independence (not to mention allowing parents shuttling kids to maintain their sanity). The Met Council is watching the technology closely, but it’s still a little too soon to tell what the opportunities will be.

Better Bikeways & Walkways

Only recently have most American cities switched their attitude toward biking and walking, from recreational activities to modes of transportation that move people in the cheapest, healthiest, and least polluting manner.

Bicycling accounts for 2.5 percent of all trips in Hennepin County, more than double the national average, and 21 percent of county residents report bicycling for transportation purposes at least once a week. A $25-million federal grant awarded in 2005 boosted the Twin Cities’ bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, as did the 2010 arrival of the country’s first large-scale bike share system, Nice Ride.

Photo via Nice Ride Minnesota

The next step, says Hennepin County’s bicycle and pedestrian coordinator Kelley Yemen, is to focus on the large category of potential cyclists described as “interested but concerned.” If this group can be made more comfortable cycling, by creating a more continuous, finer-grain bikeway system and increasing the separation of bikers from motor vehicles, Hennepin County hopes to quadruple the number of bicycle commuters to 48,000 by 2040.

By 2040, Hennepin County and Three Rivers Park District aims to…

Quadruple the number of bicycle commuters from 2010’s 12,000 people to 48,000 people by 2040.

Halve bicycle crashes per capita from 2010 levels by 2040 and move toward zero deaths on bicycle.

Bring the ratio of bike commuters who are women to half.

Complete an average of 20 miles of the bikeway system each year to have bikeway within ½ mile of 90 percent of homes in Hennepin County.

Maintain 50 percent of ridership through the winter.

Add 536 new miles in the county by 2040.

SOURCE: 2040 Hennepin County Bicycle Transportation Plan

Making a Living

Better Jobs, More Opportunity

Minnesota has consistently been a net exporter of labor—except in rare occasions. “During the late 1990s and early 2000s, we were a net importer of labor because our labor market was so tight,” says Oriane Casale, assistant director of the state’s Labor Market Information Office. “Jobs were extremely plentiful and employers were having a difficult time finding the employees they needed.” That may happen again as the boomers retire, explains her colleague Dave Senf, an employment projections analyst. Unless the state’s rate of in-migration increases, he predicts that a worker shortage could limit job growth a few years down the road. This tightening labor market should give workers more bargaining power and encourage employers to make jobs more attractive with full-time hours and benefits. Youth workers also will see more opportunities where adult workers recently have squeezed them out. Of course, striking the right balance between how much workers are paying into the social-service system and how much retirees are drawing out will be an ongoing challenge.

Less Manufacturing, More Tech & Health

In 1990, durable manufacturing contributed 10 percent of employment in Minnesota. That figure has fallen to 6.4 percent and is expected to decline to 3 percent in 20 years. Across many industries, labor is being replaced by technology, especially in retail with the advent of self-check-outs and iPad ordering. While most technical fields should see strong growth, the health care and social assistance category will experience the largest gains: In 1990, the two industries made up about 8 percent of employment, and they are predicted to increase to 17 percent by 2030.

A New Industrial Revolution

The emerging “sharing” economy turns people into producers of goods and services as well as consumers. As a result, Fisher says, there will be a blurring between living, working, and productive spaces with the most desirable located along transit corridors and adjacent to commercial amenities. “In the 20th century, people lived in suburbs and commuted to downtown and shopped in malls—it was an economy of mass production and consumption,” he notes. But today’s “economy of customizations,” Fisher adds, of more personalized goods and less mass production, means that people are living closer together but also making and selling things—everything from clothing they sew to software they code—at a global scale. Even suburban malls, including Edina’s pioneering Southdale, are diversifying by adding residential units alongside a mix of opportunity for commercial activity, services, and jobs. “I think we’ll see what I call the ‘re-aggregation’ of cities,” Fisher explains, “people living closer together and making things on a much smaller scale.”

Fisher believes the Twin Cities are well poised to adapt to the new economy as a dominant player, especially with their robotics and 3-D-printing industries, as well as active social-media culture. Michael Langley, the CEO of Greater MSP, a non-profit focused on growing the economy of the metro region, also points to the region’s strong productivity (GDP proportionately higher than population size), robust labor force (one of the highest rates of labor-market participation in the country), and strong educational system (projections suggest that 75 percent of all jobs will require some type of post-secondary credential by the next decade).

But while Langley believes the Cities have good opportunity in disruptive technologies, he suggests its stronghold may lie at the base level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the psychological theory that ranks human aspirations in order of necessity, with physiological requirements for survival being the most fundamental. Some the region’s key industry clusters focus on fundamental global issues, Langley says, noting that the Twin Cities area is home to six of the top 30 global food and agriculture companies, more water technologists than any other region in the world, and a substantial number of major health-care companies, between the Mayo Clinic, the University of Minnesota, UnitedHealthcare, Medtronic, and others. “There’s no place in the world that’s more prepared to lead on food, water, and health technology than the greater Minneapolis–St. Paul region,” he suggests.

Tom Fisher, dean of the University of Minnesota’s College of Design, is working on a book about what he calls “cities in the third industrial revolution” and sees strong potential to reverse the course of the increasingly widening inequality gap between the rich and poor. Historically, he notes, in the previous two industrial revolutions, those at the top of the economic heap who were most heavily invested in the old way of doing things tended to be the ones whose fortunes fell the furthest and the fastest. “Unless you can move to the new economy very quickly, you’re quite vulnerable,” Fisher says. “If you hold on to the old, even if you have a lot of money and power now, it’s not a good place to be. This new economy counters some of the worst aspects of the inequality that we’re seeing right now.”

She sharing economy, he explains, uses technology to help people produce goods and services with what they have—generating income from their cars and homes by driving or housing people via Lyft or Air B&B—can disperse economic opportunity. “It levels the playing field,” Fisher argues. “You don’t have to be wealthy to generate income off of property. It’s very disruptive in some ways, but very egalitarian because it empowers everybody to have the ability to reinterpret how they make a living, what they do in their house.”

Fisher cautions cities against stalling innovation by making knee-jerk reactions to new business models and rushing to put up barriers. “The political discourse hasn’t yet discovered the profound change in the economy,” Fisher says. “They’re still arguing 20th century arguments, a lot of which are irrelevant in new economy.”

Maximizing Space

Better—and Different—“Parks”

As people live closer together, public life—including public open space and access to nature and culture—becomes more important. “In the old economy, we saw these things as extras,” Fisher says. “Now they’re central to attracting and keeping talent and will be fundamental to cities like ours competing and thriving.”

The Twin Cities are among the country’s rare urban areas developed with abundant natural green space and waterways incorporated into their design. There are currently several major city park projects in the works, the flagship of which is the renovation of downtown Minneapolis’ Nicollet Mall, slated for 2016. The design vision converts the street into a more pedestrian- and bike-friendly promenade, with more dense vegetation and site-specific furniture to create gathering and performance spaces. “It’s an example of reinterpreting what a street is, as a place of gathering, not just moving,” Fisher says.

The proposed Water Works brings recreation to the downtown Minneapolis riverfront. Photo via the Minneapolis Parks Foundation, ©SCAPE and Rogers Partners

Both cities have assembled comprehensive, long-range plans for riverfront development along the Mississippi, in the hopes of turning the longtime commercial and industrial corridor into a scenic and recreational amenity. The Water Works Park proposed for the downtown Minneapolis riverfront near St. Anthony Falls, for example, adds improved pathways, an amphitheater, pavilion, and boat launch.

As a board member of the Minneapolis Parks Foundation, Fisher says he’s continually looking for creative ways to carve out more urban green space, whether in the form of temporary “pop-up” parks that would occupy a site until a building is constructed, or privately owned parks created by adjacent property owners who see how a shared public open space will enhance their property values. He also suggests that micro-parks might take advantage of under-utilized boulevards and sidewalks to grow crops and native grasses or cultivate pollinator habitats—a future that reverts the land to a state of its relatively distant past.

A rendering of the forthcoming Nicollet Mall renovation shows the street as a more pedestrian-friendly urban gathering space. Rendering via James Corner Field Operations

Savvy Redevelopment

Patrick Hamilton, the Science Museum of Minnesota’s director of global change initiatives, has been thinking intensely about cities as he plans for the development of a new traveling exhibit about their importance, surveying the past, present, and future of cities around the globe.

As a result, he sees huge opportunity in the collection of large metro sites poised for redevelopment, including the former Ford Plant in St. Paul and the old Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant site in Arden Hills. He’s encouraging the groups behind each project to coordinate their efforts and collectively brand themselves as urban innovation “test sites” for reimagining 21st century living. “What I find exciting about those sites is that they’re big enough that all of the urban infrastructure needs to be redeveloped and reconsidered,” Hamilton says. “There are opportunities to think differently about energy, water, and waste.”

Hamilton cites a new St. Paul aquaponic agriculture operation, Urban Organics, as an example of a radical approach to growing food in the city. Instead of spreading crops or ponds across a substantial acreage, the group has created an efficient, vertically integrated, closed-loop system inside the old Hamm’s Brewery building to simultaneously grow produce and raise tilapia.

Another redevelopment option Hamilton finds intriguing involves building over freeways to create developable space above. The City of Edina is currently assessing the feasibility of putting an 8-acre “lid” over Highway 100 near 50th Street that would link both sides of the city as well as add new space for housing, retail, and community activities. Minneapolis is considering the same concept for the portion of I-35W that cuts through its downtown. Although the potential lids are at least a decade out, the idea isn’t as far-fetched as it seems. Duluth took a cue from Seattle’s “Freeway Park” and successfully created Leif Erikson Park atop I-35’s tunnel, and similar “lids” have been built recently in cities as large as San Diego and Dallas.

Keeping the Lights On

Robust, Renewable Energy Resources

Unlike its neighbor to the west, Minnesota doesn’t have fossil-fuel resources and imports more than $13 billion worth of energy each year. Jason Willett, the finance and energy director of the Met Council’s environmental services division, sees this as an advantage for renewables. “We’ll be one of the leaders in this area because we don’t have a vested interest in resisting it,” he says.

The cost of wind and solar power has come down dramatically, quickly approaching cost-competitiveness with conventionally produced grid electricity. The state’s Renewable Energy Standard mandates that 25 percent of its power be generated from renewable energy sources by 2025, and Xcel Energy is on target to meet a more ambitious goal of producing 30 percent of its energy from renewables by 2020. At this point, renewables’ main limitation is storage. “The game changer will be if there’s new battery technology,” Willett notes.

Rolf Nordstrom, head of the energy nonprofit Great Plains Institute, points out that in 2013, 16 percent of Minnesota’s energy was produced by wind—ranking the state fifth in the nation. He also notes the area’s abundant solar resources, equivalent to Houston, Texas. The Minnesota Department of Commerce projects that the state’s 14 megawatts of solar-energy capacity currently installed will jump to 400 by 2020.

Nordstrom points out a few ways local government and businesses are working to help Minnesotans go solar. First, the city of Minneapolis’ efforts to map the solar potential for every building in the city so property owners can quickly assess the viability of a panel installation.

And also, 3M’s new Solar Community Initiative program for employees that offers to discount about a third of the cost of a solar-panel project as well as provide support for planning and installation—a cutting-edge “continuing education” perk.

The Climate

More Rain

As the University of Minnesota’s chief climatologist for the past three decades, Mark Seeley has studied meteorology in an area of the country that is seeing some of the most profound climate change. Precipitation is changing both in quantity and character: Not only are average annual precipitation numbers up throughout the state, but also a larger fraction is due to very intensive rainfalls. Since 2004, Minnesota has experienced three so-called “1,000-year” floods and the frequency of large storms, with more than three inches of rainfall in a day, has increased about 70 percent in the past decade. “That’s problematic for us because we don’t cope with those so well,” Seeley says, noting the inadequacy of a storm sewer system and waterway infrastructure designed to handle the climate of years past.

Hotter Temperatures

Seven of Minnesota’s 10 warmest years on record occurred in the past 15 years. The overall temperature has increased one to two degrees Fahrenheit since the 1980s and is projected to rise another two to six degrees by 2050. This increase may lengthen the growing season and expand the range of suitable plants, but it comes with an increasing number of heat advisories of serious public health consequence, Seeley warns—excessive heat results in more than 100 fatalities nationally each year and is one of the country’s top weather-related killers.

More Intentionality in Creating the Future Twin Cities

In thinking broadly about the Twin Cities’ future, the Science Museum’s Patrick Hamilton believes that, ironically, its current success may hold it back. “The biggest challenge the Twin Cities faces is that we’re pretty good—a pretty good place to live, work, and raise a family —and that can generate complacency,” he says. But when it comes to competing with other cities for the best talent and ideas, the Twin Cities contends not just with cities within the region, but around the globe. “Up until fairly recently, I’d think, ‘What’s happening in Winnipeg, Denver, Portland, Seattle?’ because I’d think of those as comparable cities,” Hamilton says. “We have to think and stretch more ambitiously. Not just for the chest-thumping sake of it, but in order to be a successful 21st century city, we have to be more intentional in how we design and create our future Twin Cities.”