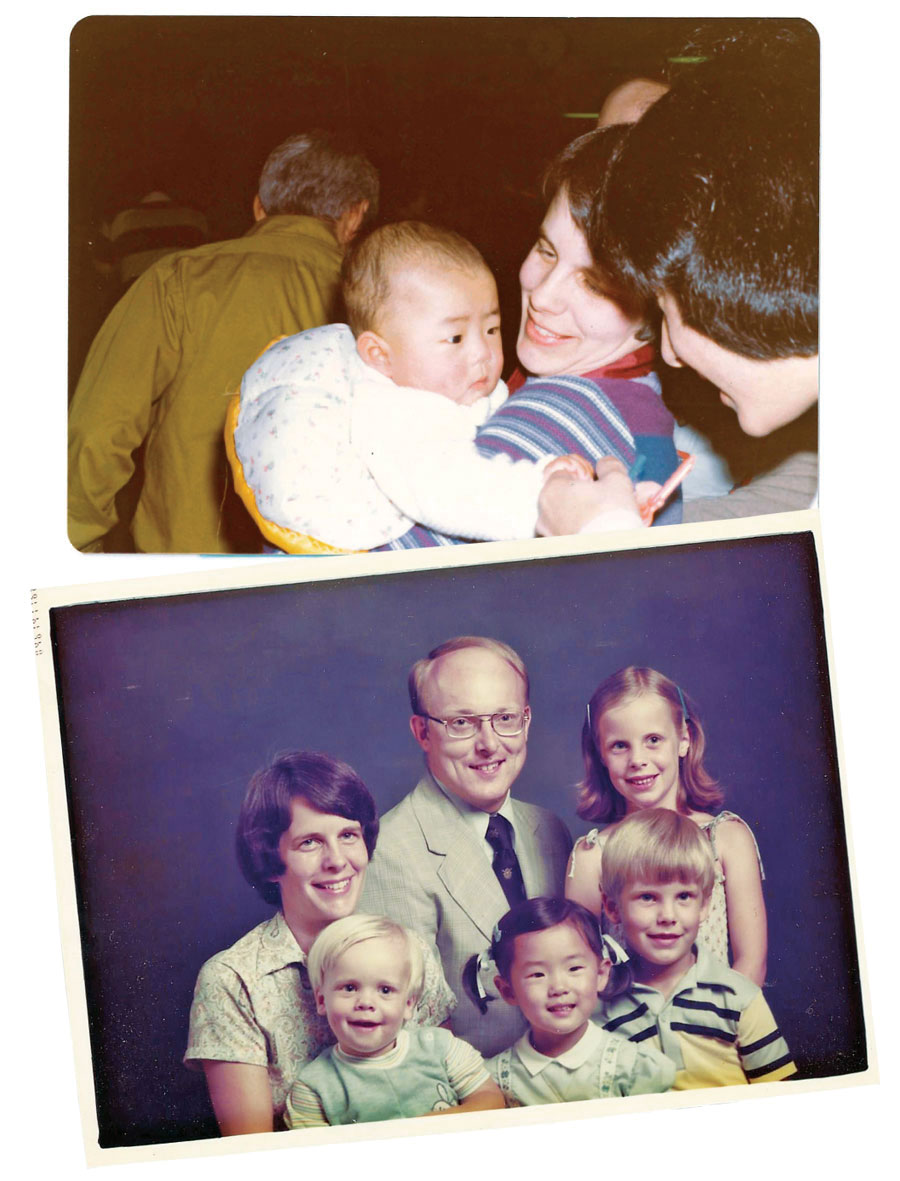

Judy Eckerle was abandoned, shortly after birth, in Seoul, South Korea. She was soon adopted, and her new family brought her to Minnesota in 1977. It was, by then, a familiar story: In the decades following the Korean War, tens of thousands of orphans were adopted, carried onto planes in Seoul, and taken abroad by grateful new parents. Many came to Minnesota, “The Land of 10,000 Korean Adoptees,” as some have taken to calling it. Growing up in Bloomington, Eckerle was one of eight Koreans in her elementary-school class. It was almost unremarkable—“super normal,” she says.

Eckerle was raised by white parents, with white siblings, a situation so typical for Koreans in Minnesota that anything else seemed strange. “There were two Koreans in my class who weren’t adopted,” she recalls, “and the rest of us adoptees were like, Weird, why are their parents Korean?”

At 16, Eckerle declared that she would become a doctor. While still a senior in high school, she spent 20 hours a week shadowing a doctor in a hospital NICU (neonatal intensive care unit). Eckerle, who talks quickly in disarmingly frank bursts, is exceedingly empathetic, especially regarding children. The NICU seemed like a good fit.

But when Eckerle was in medical school in Milwaukee, in the early 2000s, she paid a working visit to the International Adoption Clinic at the University of Minnesota’s Masonic Children’s Hospital, in Minneapolis. The same doctor she had shadowed back in high school, Dana Johnson, had founded the clinic in 1986. He had adopted an infant from India the year before, and in the process began to realize how many medical conditions were endemic to adoptees and how few specialists were available to help. In fact, there were none.

The U’s clinic was the first of its kind. Over the next 20 years, as international adoptions more than doubled, similar clinics opened around the country, and by 2006 about 200 doctors had adoption expertise. No clinic, however, had as strong a reputation as the one at the U. Johnson had pioneered much of the research in the field, becoming known as the father of adoption medicine. Adoptive parents around the world sought his expertise, and he frequently advised countries on their adoption programs.

By knowing what to look for, in photos and sometimes sparse records, the clinic can help prospective parents understand the medical issues likely to affect a child they’re considering for adoption. Vitamin deficiencies, thyroid problems, sleep disorders, fetal alcohol syndrome, anxiety, toileting problems, and early onset of puberty (perhaps a result of hormonal flooding after an extended fight-or-flight response) are all potential issues, depending on where a child has been living, among other factors. After adoption, the clinic can address them.

Without such expertise, debilitating conditions can be missed—sometimes for years. The clinic often sees teenage adoptees with long-ignored issues that have become nearly intractable. “Everyone thinks, Oh, they’re adopted and that’s just how they’re supposed to be, or that they’re always going to be traumatized,” Eckerle says. It never fails to break her heart.

Eckerle joined the clinic for good in 2007, and after a long period of mentorship she became its director three years ago. By then, however, things had changed. International adoptions to the United States had peaked in 2004 at 22,991. They now number about 5,500 a year, about a 75 percent drop.

The perception of international adoption had changed, especially among the sending nations, which stemmed the flow sometimes as a matter of pride and sometimes politics. South Korea slowed to a trickle. Guatemala closed. Russia closed.

“Three months after I became director, I had a really serious conversation with the heads of the hospital,” Eckerle says. The topic was how the clinic could adapt, to stay open. Nearly all of the other adoption medicine clinics had already closed.

“The community has a tradition of welcoming people from other countries.”

Minnesota has led the country in international adoptions per capita for years, nearly since the practice began, in the 1950s—long enough that it may now be self-perpetuating. The more you see families with adopted children, the more it seems “super normal.” One of the country’s oldest and largest adoption agencies, Children’s Home Society, is based in St. Paul. (It merged with Lutheran Social Service, which also has a strong adoption program, five years ago, due to the decline in international adoptions.)

Minnesota has extended its hospitality to refugees, from Hmong to East Africans, and its officials have reaffirmed the state’s openness to immigration in the face of recent resistance. “It’s a community that has a tradition of welcoming people from other countries,” says Eckerle, though the reasons behind it are something “no one’s ever pinned down exactly.” Scandinavian notions of inclusivity? Lutheran probity or compassion? At this point, it is what it is.

Some adoptees are now questioning the process that brought them here. Hundreds of Korean adoptees have returned to their homeland in recent years, including author Jane Jeong Trenka, who was raised in northern Minnesota and believes her birth country made it too easy to separate her from her roots. Her lobbying in South Korea helped change the country’s adoption policy in 2012, squeezing the number of adoptions to other countries from roughly a thousand a year to a couple hundred, even as the number of abandoned babies began to rise.

Eckerle’s adoptive parents had a closer relationship with her home country than most Americans. Her father was in the U.S. Army and was stationed in South Korea. Her mother taught English in South Korea. They knew the language, the food, the culture. They gave Eckerle a hanbok, the colorful traditional Korean dress, when she was a little girl, and the family enjoyed Asian food when celebrating special occasions.

But Eckerle was not nostalgic for the country where she’d been abandoned a week after her birth. She had left before she was 6 months old. “Frankly, I wasn’t that interested,” she says. “Once a year my mom would say, ‘Let’s celebrate your anniversary!’ and I’d say, ‘Okay,’ and the rest of the year I was pretty uninterested in anything Korean.”

That was true until she graduated from college, when her parents gifted her a trip to South Korea. Even then, the destination wasn’t especially important to her. “My parents could have said, ‘Here’s a trip to Paris,’” Eckerle recalls, “and I would have said the same thing: ‘Great! Sounds like fun!’”

The trip, however, transformed her. “My first thought was that I was home,” she says. “I really truly in my heart felt like this was where I was supposed to be. It was never a disowning of my family or the people that I loved in Minnesota, it was just such an immediate connection.”

Part of that, she allows, was being in her early 20s, searching for an identity. But over the next three years, she returned every few months. She would waitress and nanny back in the U.S., then gather her money and go to Korea. She learned Korean, worked at an orphanage near Seoul, and, like many Korean adoptees, intensively searched for her birth parents.

On one of her early trips, Eckerle met a producer of a Korean cable-TV network, who made an hour-long special on her life and her birth-parent search—complete with church ladies hired to sit in the audience and cry at especially dramatic moments (“very Korean,” Eckerle says). Her story was a hit, and she retold it for every major newspaper and morning TV talk show in the country.

“There was a point when I couldn’t walk into a restaurant in Seoul without a little old lady coming up and patting me and saying she was sorry,” she says. “My face was everywhere. I even got a Korean stalker from prison who said he was my advocate. I was way overexposed for a while.”

Yet her story elicited no breakthroughs. No one came forward to claim her. No tips. Nothing.

In the midst of her unexpected celebrity, Eckerle began medical school in Wisconsin. And she took on another venture: pageants. It was partly a distraction from the seriousness of school and partly a bargaining chip. She’d come to see Korean media coverage as essential to her search, and knew she would need some new twist to get more of it. Koreans love pageants. So, she vied for Miss America.

That, too, turned dramatic. Eckerle actually won the Wisconsin pageant, and was signing the paperwork when the coordinator noticed that she was a week older than the recently changed rules allowed. She had to give back the crown. Then she competed in the other major pageant, Miss USA—and she won that, too. She was Miss Wisconsin USA in 2003.

She got more coverage in South Korea. But only one family came forward—an obvious mismatch, and DNA tests proved it. And that was that. Eckerle had gone about as far as any adoptee could down this particular road. So, after residency in New York, she went to work in Minneapolis, determined to help other adoptees down other roads, without ever losing sight of her own destination.

The adoption medicine clinic is in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis, in one of the Lego-like buildings of interchangeable corridors and exam rooms glommed onto the Masonic Children’s Hospital. But essentially it’s ad-hoc. It’s Eckerle and whomever she needs to pull in: a physician, a psychologist, an occupational therapist, a physical therapist, a nurse coordinator. Much of her work is done over the phone or email. She has one-fifth of an administrative assistant.

When I meet Eckerle, she’s sitting in a small conference room where she often works. She had just run out of cupcakes, decorated with Korean and American flags, that her mother dropped off to celebrate Eckerle’s arrival in Minnesota 40 years ago.

The clinic might not exist at all had Eckerle not recognized, shortly after becoming director, that the most intriguing trend at the clinic wasn’t the drop in international adoptees but the concurrent rise in foster children and domestic adoptees. Foster care placements have increased since 2013, especially in Minnesota, largely owing to parental substance abuse and neglect. Yet foster children and domestic adoptees still only comprised about 10 percent of the clinic’s patients when Eckerle took over. When Eckerle began to talk with U administrators about the future of the clinic, she saw a need—and an opportunity.

The medical and psychological issues can be similar among orphaned children, whether foreign or domestic. But most adoption clinics weren’t serving foster kids or domestic adoptees, mostly because they didn’t have the means. “It’s not a lucrative business to see people on medical assistance,” Eckerle notes. As the other clinics began to close, Eckerle became more determined to stay open.

Eckerle simplified the clinic’s name to the Adoption Medicine Clinic, to signal its broader mission. And the increased focus on foster and domestic adoptive families has kept Eckerle busy—these patients now make up about 50 percent of her caseload. “I think it would have been really tragic if we’d closed as well simply because no one’s going to make money on it,” says Eckerle. “For me, that wasn’t a compelling enough reason.”

The rest of her cases are international, and, as other clinics have closed, the U has nearly cornered that market, too—“sadly,” Eckerle says. In any given month, Eckerle might see kids from as far away as Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and Ireland.

Denise and Zach Bielke, of Minneapolis, were introduced to Eckerle by their social worker at the start of the adoption process. Eckerle walked them through a checklist of medical conditions endemic to the countries where they were looking, so they could decide what they’d be willing to take on. When they began to get referrals—pictures and records of kids available for adoption—they consulted with Eckerle again before adopting Eleanor from China. They brought her home in 2014 at age 2.5.

Six days later, they took her to Eckerle, who checked her for vaccinations and parasites, among other things. Almost all adoptees from China now have special needs, and Eleanor is no different. She has major gastro-intestinal issues, and went into a 10-hour surgery within months of arriving in Minneapolis to remove a cyst on her liver, which had grown into other parts of her intestine as well as her pancreas.

A few days later, Eleanor developed a blood clot in her leg, and will likely need to see a hematologist—an expert in blood disorders—for the rest of her life. But Denise counts her family among the lucky ones. “Eleanor is doing great, she’s healthy, she’s happy, she’s smart,” says Denise. “We know what the future holds for her, and it’s possible that includes other surgeries. But we know we’ll be well-taken care of.”

Most kids are on referral lists now precisely because of their medical needs, even as most adoption specialists have closed up shop. (Healthy children being more likely than ever to be adopted in their own country or kept by their parents, especially since China eased its one-child policy in 2015.) For Eckerle and her crew, the pressure to stay open has become personal—many have adopted or are adoptees. They know the road their clients are on; indeed, they may still be traveling it themselves.

At the end of last year, a crew from MBC—the NBC of South Korea—came to the U to interview Eckerle. They wanted to know about the clinic, and why so many Korean adoptees had wound up in Minnesota. Then, a few weeks later, they asked her to be the narrator and star of their documentary. Eckerle hadn’t been seeking to reopen her search, to expose herself to more disappointment. But she couldn’t say no either. “What if this time it works?” she says. “I never close a door.”